It's Not Our Sandbox :: Auditing Foxit Reader's PDF Printer For an Elevation of Privilege

Mid last year, I blogged about how I found an exploitable use-after-free in Foxit Reader and how I was able to gain remote code execution from that vulnerability. Then, as the second installment I blogged about a command injection in Foxit Reader SDK ActiveX. In the spirit of catching foxes, I decided to look at a new component in Foxit Reader later in that same year. To my (un)surprise, I was able to discover several vulnerabilities in this component that could allow for a limited elevation of privilege, one being particularly nasty. That lead to this, third installment.

TL;DR; I walk through the attack vector, analysis and exploitation of CVE-2018-20310 which is a stack based buffer overflow in the PDF Printer when sending a specially crafted proxyDoAction request.

The Version

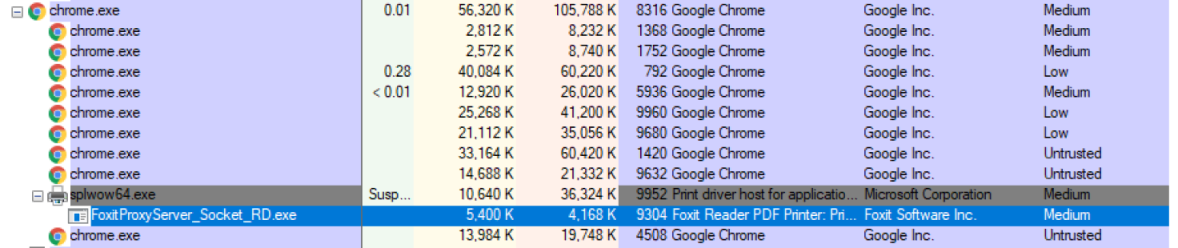

I tested version 9.3.0.912 of Foxit Reader with SHA1 of the FoxitProxyServer_Socket_RD.exe binary being: 0e1554311ba8dc04c18e19ec144b02a22b118eb7. At the time, this was of course the latest version.

The Vector

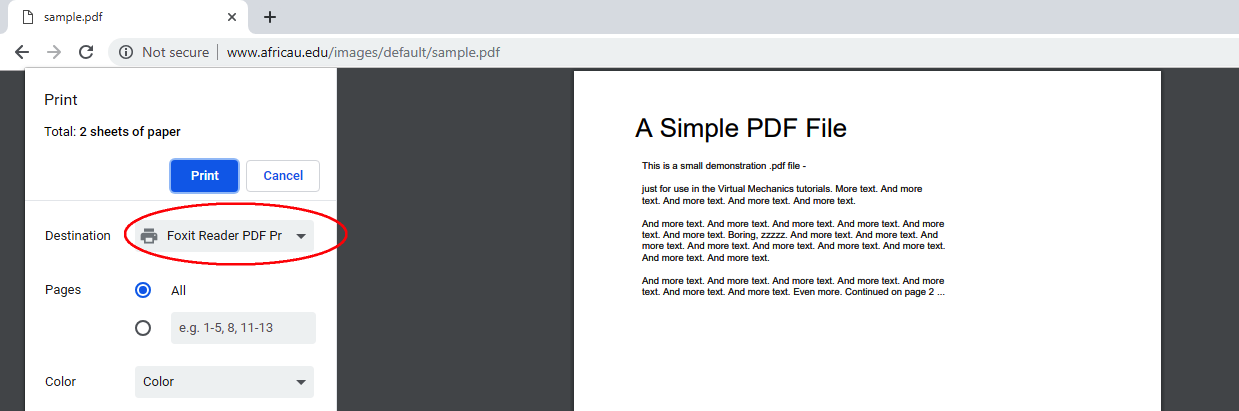

The PDF Printer is a relatively undocumented feature within Foxit Reader and is primarily used to handle print requests to a PDF file from any application. Once Foxit Reader is installed, the Foxit PDF Printer is the default printer used for handling print jobs.

This essentially means that the FoxitProxyServer_Socket_RD.exe binary will be started, at medium integrity for a brief second.

That brief second is due to the server listening on localhost port 50000 by default and accepting only a single request. Once a request is made, it closes the port and terminates execution. This gives an attacker executing code in a render tab a kind of race condition window, when the user attempts to print to PDF using the Foxit PDF Printer.

After more investigation into the issue, I later found out you can make calls to CreateDC API from some sandboxed processes to get a printer device context and then later create a print job with the default printer. This means that an attacker doesn’t even need to race a request to the FoxitProxyServer_Socket_RD.exe binary at all.

The Vulnerability

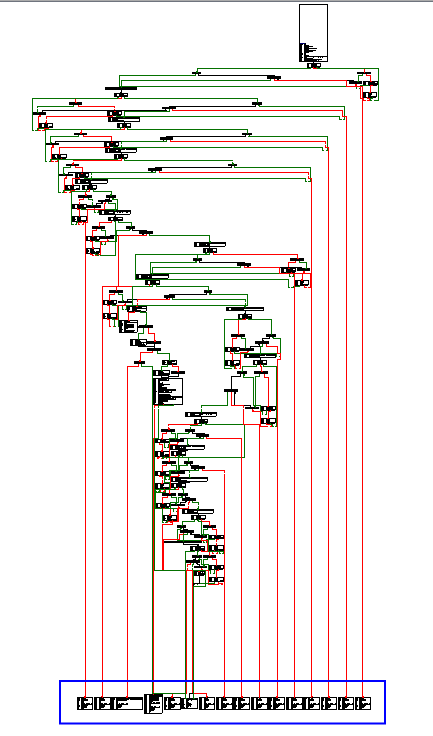

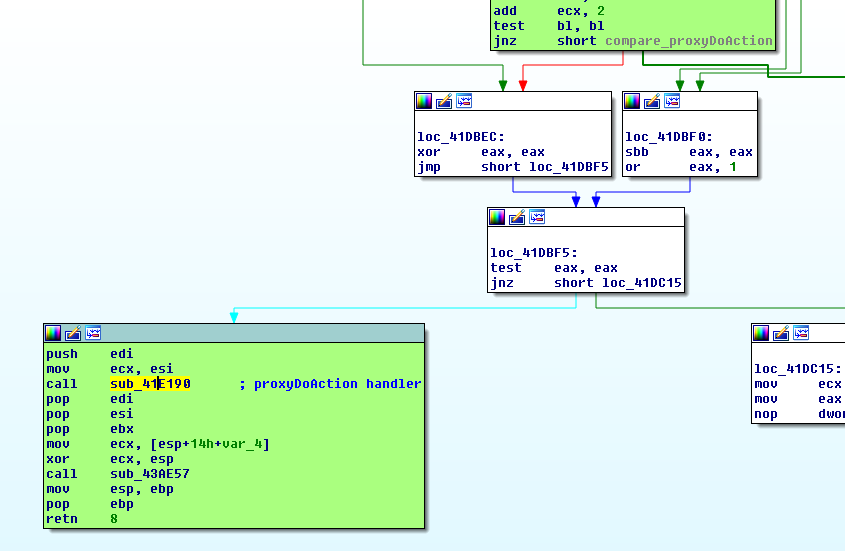

After sniffing some sample requests sent to port 50000 while attempting to print a page from a browser, I found the following important function, sub_41DBA0.

This function handles several different type of requests and the handlers are highlighted in blue in this function:

- proxyDoAction

- proxyPreviewAction

- proxyPopupsAction

- proxyCPDFAction

- proxyUpdatePreview

- proxyFinishPreview

- proxyCollectSysFont

- proxyGetImageSize

- proxyCheckLicence

- proxyGetAppEdition

- proxyInitLocalization

- proxyCreateDirectoryCascade

- proxyIEMoveFileEx

- proxySendFileAsEmailAttachment

Whilst some of these really stood out as highly exploitable functions, it wasn’t always possible to reach the vulnerable API. Let’s take proxyIEMoveFileEx for example. The function accepts three (3) arguments and is essentially a MoveFileExW call without any checks. The problem was however, I couldn’t generate a packate structure that would reach the MoveFileExW. I would always hit an out of bounds read before reaching this bug and it appeared like the function wasn’t working like the developers intended otherwise it would have been an easy to exploit logical vulnerability. Below is the location of the underlying API:

.text:00420C85 loc_420C85: ; CODE XREF: sub_420930+331

.text:00420C85 push ebx ; dwFlags

.text:00420C86 push edi ; lpNewFileName

.text:00420C87 push eax ; lpExistingFileName

.text:00420C88 call ds:MoveFileExW

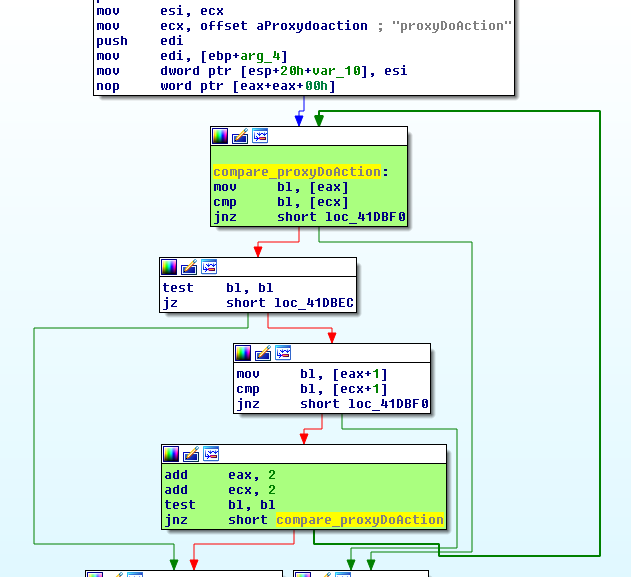

After doing some more reversing, I quickly learnt that the proxyDoAction was also an interesting function because it took an opcode that allowed an attacker to reach five (5) different additional code paths. Below is the check for the proxyDoAction string in the request packet:

Providing a correctly formatted request means we can eventually we can reach the handler:

Inside of the handler, we can see it accepts three 3 arguments:

Once we dive into the function, we can see when processing the 3rd argument what is happening:

.text:0041E407 mov esi, [eax] ; eax is a ptr to our buffer

.text:0041E409 jmp short loc_41E421 ; take jump

.text:0041E40B ; ---------------------------------------------------------------------------

.text:0041E40B

.text:0041E40B loc_41E40B: ; CODE XREF: sub_41E190+275

.text:0041E40B xor esi, esi

.text:0041E40D test eax, eax

.text:0041E40F jnz short loc_41E421

.text:0041E411 call sub_64BE4A

.text:0041E416 mov dword ptr [eax], 16h

.text:0041E41C call sub_65015F

.text:0041E421

.text:0041E421 loc_41E421: ; CODE XREF: sub_41E190+279

.text:0041E421 ; sub_41E190+27F

.text:0041E421 lea eax, [edi+4] ; calculate offset to src ptr

.text:0041E424 mov [ebp+var_80_opcode], 0 ; initialize dst buffer

.text:0041E42B add eax, ebx ; recalculate offset to src ptr

.text:0041E42D lea ecx, [ebp+var_80_opcode] ; fixed buffer of size 0x4

.text:0041E430 push esi ; size, controlled from our buffer

.text:0041E431 push eax ; src ptr to copy from

.text:0041E432 mov edx, esi

.text:0041E434 call sub_41CB30 ; call sub_41CB30

.text:0041E439 add esp, 8

.text:0041E43C push [ebp+var_80_opcode] ; opcode

.text:0041E43F push [ebp+var_84] ; int

.text:0041E445 push [ebp+lpFileName] ; lpFileName

.text:0041E44B call sub_4244C0 ; proxyDoAction second handler

The call to sub_41CB30 looks suspicious since its using a size value and a source buffer as arguments. Also, we can see that the destination buffer is stored in ecx. When we investigate sub_41CB30, we can start to see what is happening:

.text:0041CB30 sub_41CB30 proc near ; CODE XREF: sub_41D500+185

.text:0041CB30 ; sub_41D740+11A

.text:0041CB30

.text:0041CB30 arg_0_src = dword ptr 8

.text:0041CB30 arg_4_size = dword ptr 0Ch

.text:0041CB30

.text:0041CB30 push ebp

.text:0041CB31 mov ebp, esp

.text:0041CB33 push esi

.text:0041CB34 mov esi, [ebp+arg_4_size] ; store controlled size in esi

sub_41CB30 is setting up a call to sub_645BD0 using source, destination and size. Source and size are totally attacker controlled and the destination is a local stack variable from sub_41E190.

.text:0041CB61 loc_41CB61: ; CODE XREF: sub_41CB30+16

.text:0041CB61 push ebx

.text:0041CB62 mov ebx, [ebp+arg_0_src] ; set the src in ebx

.text:0041CB65 test ebx, ebx

.text:0041CB67 jz short loc_41CB7F

.text:0041CB69 cmp edi, esi

.text:0041CB6B jb short loc_41CB7F

.text:0041CB6D push esi ; size

.text:0041CB6E push ebx ; src

.text:0041CB6F push ecx ; dst

.text:0041CB70 call sub_645BD0 ; call sub_645BD0

sub_645BD0 is more or less an inline and custom memcpy implementation and we eventually reach the following code block:

.text:00645C14 loc_645C14: ; CODE XREF: sub_645BD0+2F

.text:00645C14 bt dword_932940, 1

.text:00645C1C jnb short loc_645C27

.text:00645C1E rep movsb ; stack buffer overflow!

.text:00645C20 mov eax, [esp+8+arg_0]

.text:00645C24 pop esi

.text:00645C25 pop edi

.text:00645C26 retn

Triggering the Vulnerability

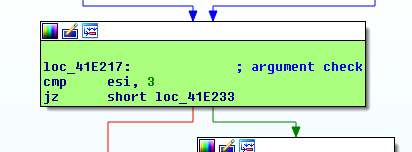

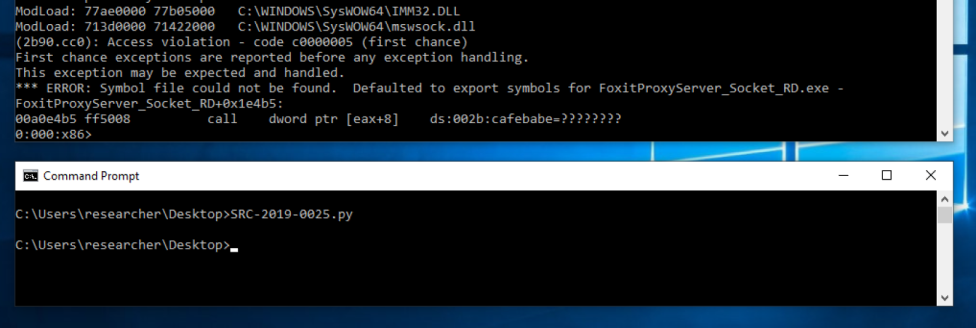

Since we can run the executable outside of the sandbox, I found it easier to debug the application with the following command:

C:\>cdb -c "g;g" "C:\Program Files (x86)\Foxit Software\Foxit Reader\Plugins\Creator\FoxitProxyServer_Socket_RD.exe" 50000

By default the application uses port 50000 but you can also specify the port on the command line.

So essentially, sending a specially crafted request with a buffer of size 0x1000 as the opcode will trigger a stack based buffer overflow.

Exploitation

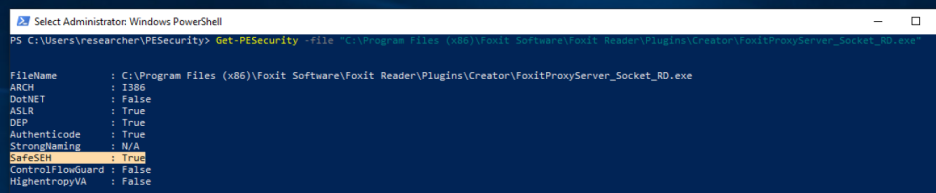

We can’t exactly (ab)use the SEH handler here:

Also, if we dive into the proxyDoAction handler again, we can see at the end of the function there is a call to sub_43AE57.

.text:0041E510 loc_41E510: ; CODE XREF: sub_41E190+8E

.text:0041E510 ; sub_41E190+9E

.text:0041E510 mov ecx, [ebp+var_C]

.text:0041E513 mov large fs:0, ecx

.text:0041E51A pop ecx

.text:0041E51B pop edi

.text:0041E51C pop esi

.text:0041E51D pop ebx

.text:0041E51E mov ecx, [ebp+var_14]

.text:0041E521 xor ecx, ebp ; xor cookie with frame pointer

.text:0041E523 call sub_43AE57

.text:0041E528 mov esp, ebp

.text:0041E52A pop ebp

.text:0041E52B retn 4

.text:0041E52E ; -----------------------

Which, as you guessed, does a cookie check:

.text:0043AE57 sub_43AE57 proc near ; CODE XREF: sub_413FA0+5D

.text:0043AE57 ; sub_413FA0+7B

.text:0043AE57 cmp ecx, ___security_cookie ; bummer

.text:0043AE5D repne jnz short loc_43AE62

.text:0043AE60 repne retn

.text:0043AE62 ; ---------------------------------------------------------------------------

.text:0043AE62

.text:0043AE62 loc_43AE62: ; CODE XREF: sub_43AE57+6

.text:0043AE62 repne jmp sub_43B739

.text:0043AE62 sub_43AE57 endp

However, if we look past the vulnerable function, we can see something interesting:

.text:0041E4A2 loc_41E4A2: ; CODE XREF: sub_41E190+2F0

.text:0041E4A2 mov byte ptr [ebp+var_4], 8

.text:0041E4A6 cmp [ebp+var_24], 0

.text:0041E4AA jnz short loc_41E4B8

.text:0041E4AC mov ecx, [ebp+var_28] ; code execution primitive 1

.text:0041E4AF test ecx, ecx

.text:0041E4B1 jz short loc_41E52E

.text:0041E4B3 mov eax, [ecx]

.text:0041E4B5 call dword ptr [eax+8] ; eop

.text:0041E4B8

.text:0041E4B8 loc_41E4B8: ; CODE XREF: sub_41E190+31A

.text:0041E4B8 mov byte ptr [ebp+var_4], 9

.text:0041E4BC mov ecx, [ebp+var_28] ; code execution primitive 2

.text:0041E4BF test ecx, ecx

.text:0041E4C1 jz short loc_41E4DB

.text:0041E4C3 mov edx, [ecx]

.text:0041E4C5 lea eax, [ebp+var_4C]

.text:0041E4C8 cmp ecx, eax

.text:0041E4CA setnz al

.text:0041E4CD movzx eax, al

.text:0041E4D0 push eax

.text:0041E4D1 call dword ptr [edx+10h] ; eop

If we overwrite var_28 from our stack overflow and don’t overwrite the return address or exception handler then we can fake an object and redirect code execution via a vtable call. This works because var_28 is lower down the stack:

-00000080 var_80_opcode dd ? ; pwned

-0000007C var_7C db 36 dup(?) |

-00000058 var_58 dd ? | overflow direction

-00000054 var_54 db 8 dup(?) |

-0000004C var_4C db 36 dup(?) v

-00000028 var_28 dd ? ; pwned also!

-00000024 var_24 db 8 dup(?)

-0000001C var_1C dq ?

-00000014 var_14 dd 2 dup(?)

-0000000C var_C dd 2 dup(?)

-00000004 var_4 dd ?

We can calculate the size of the var_80_opcode variable being 0x80 - 0x7c = 0x4 bytes in stack size. But it gets even easier! Let’s look at the code just before the overflow:

.text:0041E34D loc_41E34D: ; CODE XREF: sub_41E190+1A2

.text:0041E34D ; sub_41E190+1AB

.text:0041E34D lea eax, [esi+1]

.text:0041E350 add ebx, 4

.text:0041E353 push eax

.text:0041E354 call sub_43AEAB

.text:0041E359 mov [ebp+var_84], eax

.text:0041E35F add esp, 4

.text:0041E362 lea eax, [ebp+var_84]

.text:0041E368 mov [ebp+var_E4], offset off_8F3140

.text:0041E372 mov [ebp+var_E0], eax

.text:0041E378 lea eax, [ebp+var_E4]

.text:0041E37E mov [ebp+var_C0], eax

.text:0041E384 lea eax, [ebp+var_4C] ; overflowed pointer loaded

.text:0041E387 mov [ebp+var_28], 0

.text:0041E38E mov [ebp+var_90], eax

.text:0041E394 push eax

.text:0041E395 lea ecx, [ebp+var_E4]

.text:0041E39B mov byte ptr [ebp+var_4], 5

.text:0041E39F call sub_421D60

.text:0041E3A4 mov [ebp+var_28], eax ; bingo! We can fake an object!!

.text:0041E3A7 mov [ebp+var_24], 0

.text:0041E3AB mov byte ptr [ebp+var_4], 6

.text:0041E3AF mov ecx, [ebp+var_C0]

.text:0041E3B5 test ecx, ecx

.text:0041E3B7 jz short loc_41E3DA

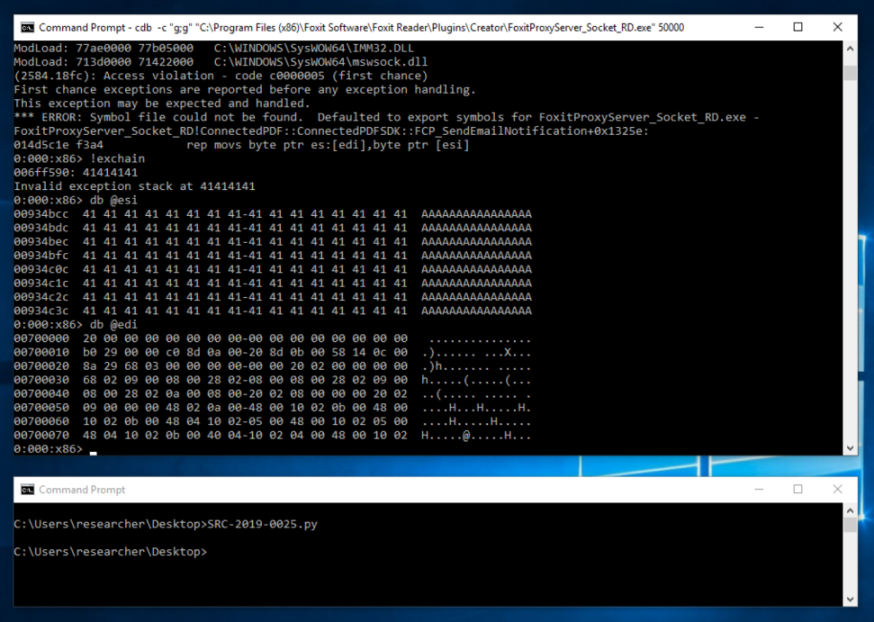

What is happening here is that we can leverage var_4C (which will be overflowed) to fake an object because a pointer to it is later stored in var_28. This means we only have to overflow by 0x80 - 0x4c = 0x34 bytes! Now, if we update our poc, we can smash the variable on the stack and redirect execution flow:

We still have the issue of ASLR which I didn’t bother to address since the impact of the vulnerability was limited anyway, but its a good example of when things can go wrong, despite all the proper mitigations.

I also used a modified version of the mayhem library by @zeroSteiner to inject my poc into a sandboxed process (along with python) to demonstrate to the Foxit developers the true impact.

If you want to test this out, you can download the poc trigger.

Conclusion

This was not just a vulnerability within Foxit Reader, but rather how third party applications trust installed print servers to be a safe boundary. Attacking new or unexplored components often yields highly exploitable findings but getting access to the interface can be the hardest challenge to a researcher.